The Groove 252 - Who Decides What Counts as Art?

Welcome to the 252nd issue of The Groove.

I am Maria Brito, an art advisor, curator, and author based in New York City.

If somebody forwarded you this email, please subscribe here, to get The Groove in your inbox for free every Tuesday.

WHO DECIDES WHAT COUNTS AS ART?

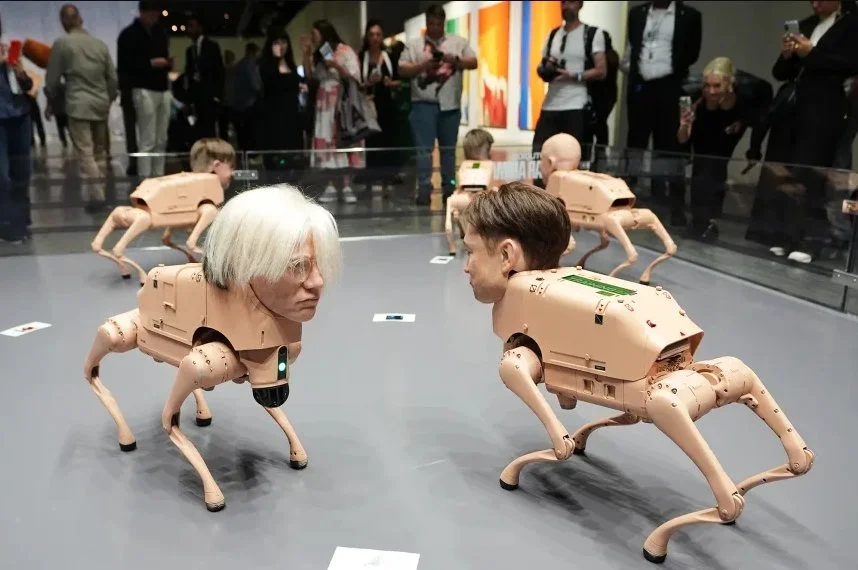

Regular Animals, 2025. Beeple’s robot dogs inside their pen at Art Basel Miami Beach last week.

Miami gave us a perfect storm this year: beach-level humidity, the heaviest traffic, and VIP lines long enough to qualify as an endurance sport. A mix of blue-chip, historical references and discoveries lined the hallways of the main fair and the satellite ones.

Front and center, Mike Winkelmann (aka Beeple), the artist whose NFT sold for $69.3 million in 2021, staged the week’s most talked-about spectacle: a pen of robot dogs, priced and sold out at $100,000 each, trotting around with the uncanny faces of tech and art celebrities: Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol and of course, Beeple himself.

Depending on whom you asked, they were either the end of civilization or the most honest mirror we’ve had in years. That’s the point: the fight wasn’t really about “is this art?” but about who gets to decide what counts, how attention is engineered, and why the most Instagrammed objects keep hijacking the conversation.

The Dog in the Room: What Spectacle Is For

Art Basel created a new section in the Miami Beach Convention Center called Zero 10, dedicated to digital art. The highlight (or lowlight) was Beeple’s dog pen. Each dog houses a camera that scans its surroundings, processes what it “sees,” and then spits out a print in the style of the artist or “overlord” it represents.

The dogs themselves can last indefinitely, but the cameras won’t; they’re expected to stop working in about three years. Beeple has said he wants owners to take the dogs out into the world. I think it would be great if they did; imagine a follow-up installation built from those images once the three years are up.

Part of Beeple’s argument is that, once upon a time, Picasso and Warhol, two of the most prolific artists in history, told us what “good” looked like and changed the course of the canon with their images. Today, billionaires like Zuckerberg and Musk control the algorithms that shape what we see and capture our attention, effectively becoming the most powerful curators of our time.

Beeple didn’t fall from the sky; he’s the logical sequel to a long line of artists who understood that, in modern culture, form and format are inseparable from attention. Marcel Duchamp turned a urinal into a sculpture in 1917, a lever that moved the boundary line of art. That gambit, call it conceptual aikido, reshaped the century.

If you need a Miami-specific prequel, remember Maurizio Cattelan’s 2019 “Comedian”: a banana taped to a wall produced in editions of three that sold for $120,000 a pop. And then, in our own age of memetic finance, it rocketed to a $6.2 million result at auction last year. Outrage was the medium; virality, the accelerant. The banana wasn’t great because it was a banana. It was great (or infuriating) because it clarified how value is minted in public: through spectacle, scarcity, and nerve.

Beeple’s dogs slot neatly into that lineage. They’re engineered to harvest and redistribute attention, and they arrived in a fair that carved out a dedicated digital zone where much of the work looped back on itself: tech about tech about tech. That self-reference is the hazard of the genre; the risk is that the spectacle eats the subject. But the larger function is diagnostic: it shows the market to itself.

Who Gets to Say “This Is Art”? (And Why That Keeps Changing)

We’ve been arguing this for a century, and the arguments keep getting better. Duchamp said it plainly in 1957: “The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world.” In other words, meaning isn’t issued; it’s negotiated.

Andy Warhol added the other half of the equation: “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” You don’t have to like that to learn from it. It’s an art economy where distribution is half the artwork and the market is theater. Placement, release, reception, it all becomes part of the art’s meaning.

But here’s the tension Miami laid bare. As Nobel Laureate and American economist Herbert Simon warned in 1971, “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” Platforms don’t just show us art; they ration our seeing. Beeple’s own line that the “overlords” who run the algorithm are today’s supreme curators lands because it’s true. The fight over the dogs wasn’t only about aesthetics. It was about sovereignty: who controls the lens you look through.

Where to Look When Everything Competes for Attention

So what do we do with a circus? First, strip the gimmick and test the core. If you subtract the hardware, does an idea remain that holds in a quiet room? Duchamp’s “Fountain” still does. Warhol’s systems still do. Even Cattelan’s banana, annoying as it was, distilled a thesis about price, permission, and shock. That’s the standard: after the decibels drop, is there an argument worth keeping?

Second, widen the frame beyond the dog pen. Attention-harvesting art can clarify the ecosystem, but it isn’t the ecosystem itself. Miami also delivered museums and foundations programming, real depth, and booths where you could trace lineages across generations from Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini’s surrealism to Latin America in the 1950s.

Finally, remember that every loud object is a data point, not a destiny. Treat it like fieldwork. Note how it travels, who installs it, what texts accrue, whether institutions commit, and how the market behaves once the cameras move on. Then decide if it earns a place in your mental collection or your real one. The circus comes to town every December. The job is to leave with your taste sharpened, not your patience frayed.