The Groove Issue 63 - The Creative Value of Not Fitting In

THE CREATIVE VALUE OF NOT FITTING IN

Work that is original won’t often fit in. At least not in the beginning. This is a good thing.

If you aim for intentionally doing what other people are not doing, that is the currency of a contrarian. If you identify as a freethinker, it doesn’t matter what field you belong to; you go against the grain because you have something that you believe in, that is better than the alternative.

Throughout history, art movements have always been spearheaded by a bunch of contrarian people who went against what the previous one did: the impressionists wanted nothing to do with the romantics, the cubists didn’t want to ever be associated with the impressionists, abstract expressionists loathed any comparison to cubists or impressionists, pop artists reacted against the dryness of abstract art.

You see, these people didn’t want to fit in, certainly not with what was considered the standard of the moment. The one thing in common that these artists and creatives had is that they found peers, their own niches of like-minded people.

But what if you are an individualist in your vision? Lone wolfs have also made waves in history. Here are three:

A Peerless Contrarian Who Defied Classifications

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586–1588) is El Greco's best known work. The artist painted himself on the left directly behind the knight who is raising his hand.

You know you have hit a moment when there are no real categories to pigeonhole what you do.

Imagine in the 16th century, when all these changes happened more subtly, a Greek man who moved from his native Crete, to Venice, then to Rome and Toledo, and decided to go against everything that had been done in art before.

That man was Domḗnikos Theotokópoulos, AKA El Greco. He had been trained in a post-Byzantine art school and had studied the artists of the Italian Renaissance, but as soon as he moved to Italy, he was like: “No, I won’t follow the footsteps of the Italian masters, I’ll do my own thing.”

Romans were not kind to El Greco, because they didn’t accept that he challenged Michelangelo’s style.

The Opening of the Fifth Seal (1608–1614) which belongs to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, has been suggested to be the prime source of inspiration for Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

But once in Toledo, he started getting commissions from churches and art patrons, and judging by the amount of people who came asking for his work, his art caught fire: his signature of elongated, phantasmagorical figures seen from different perspectives and strong and saturated colors used in a very striking way became favored because nobody had seen anything like it before.

Like any good contrarian, El Greco always trusted his imagination and intuition over rules and formal principles.

But his true legacy came to light centuries after his death, when many artists like Cézanne, Renoir and Picasso claimed that El Greco discovered a realm of new possibilities. Modern scholars added that all the generations that followed him live in his realm, and as an artist he is so individual that he belongs to no conventional school. El Greco exists alone in his own category.

Never Follow the Crowd

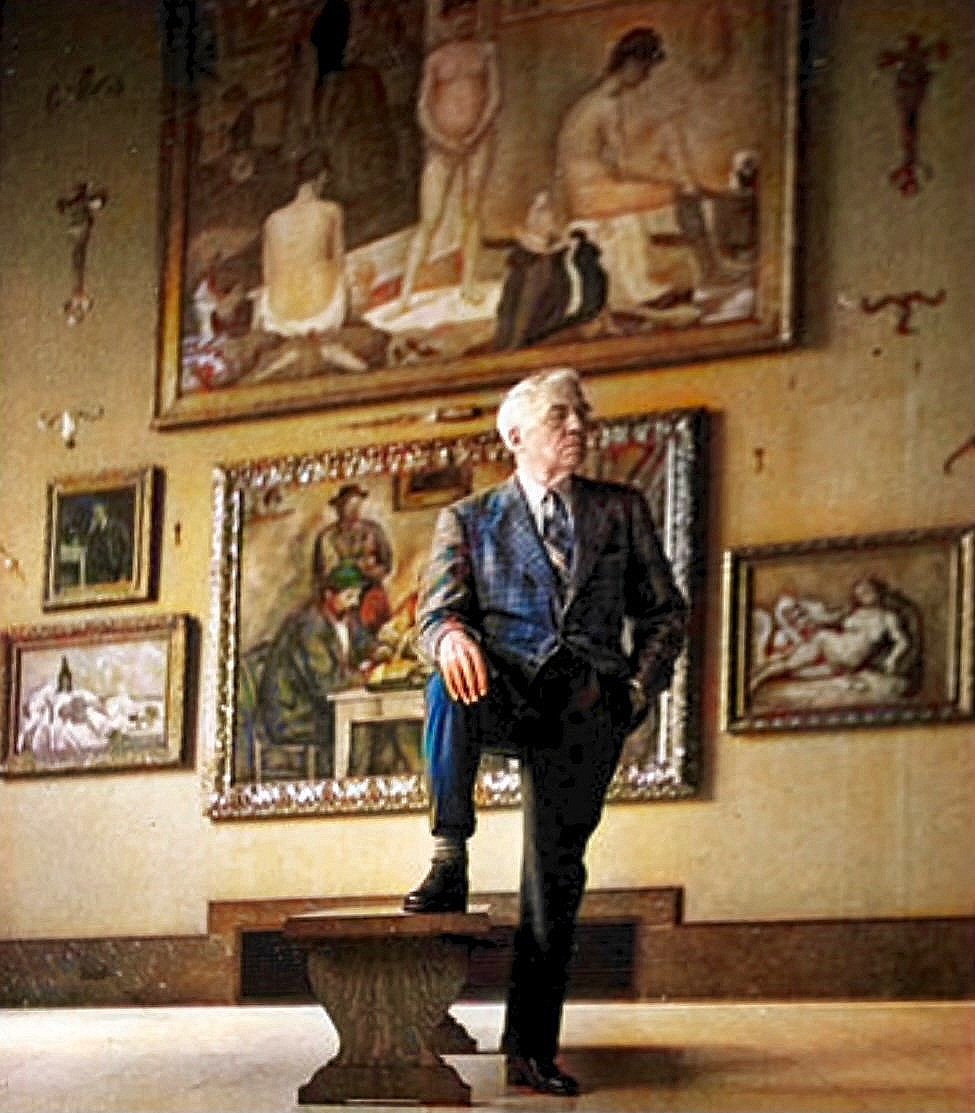

Albert C. Barnes surrounded by his collection in Merion, PA ca. 1930.

Following the crowd is a very human and very safe option, but I’m sure you know it’s the least exciting and consequently the least rewarding way to achieve something meaningful.

Albert C. Barnes never followed the crowd. He made a fortune by developing and patenting an antiseptic in the early 1900s and was a man who deeply believed in education. It occurred to him that he could help people learn through art.

After having so much surplus, he set out to create an ambitious art collection.

In 1911, Barnes reconnected with his high school classmate William Glackens and in January 1912, just after turning 40 years old, Barnes sent him to Paris with $20,000 (roughly $560,000 today) to buy paintings for him. Glackens returned with 33 works of art.

This treasure trove of artworks got Barnes so excited about collecting that he started taking those trips himself. He met Gertrude and Leo Stein and purchased his first two Matisse paintings from them.

Then, Barnes bought his collection of African art from art dealer Paul Guillaume. This triggered a desire in Barnes in collecting Harlem Renaissance and African American artists (something nobody did at that time).

The collection grew and grew and in 1923, he lent works by Picasso, Soutine, Modigliani, and Matisse to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Critics were appalled by his selections and the collection was mocked. They called it “debased art,” “incomprehensible masses of paint,” “trash,” “painted by the 'dregs of humanity,'” and “emotionally and physically sickened…as if the room were infested with an infectious scourge”.

He was peerless in his art choices and unanimously made fun of by the supposed “connoisseurs”. Throughout his life, he was misunderstood and considered by many as a dilettante.

Barnes would tell a journalist years later, “Remember these will be the Old Masters of the future”.

But, as we can now look back, this is just a sample of what Barnes was able to buy in his lifetime: 181 works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 69 works by Paul Cézanne, 59 works by Henri Matisse, 46 works by Pablo Picasso, and 7 paintings by Vincent Van Gogh. And that is just to name a handful. Barnes assembled one of the most important 20th century and African art collections in the world, and it’s now valued in billions of dollars.

The Power of Being a Contrarian For the Right Reasons

Michael Burry went to medical school and worked as a Stanford Hospital neurology and pathology resident but realized that his heart was not into being a physician and decided start his own hedge fund.

In November 2000, Burry opened Scion Capital, funded by an inheritance and loans from his family.

He was paying close attention to the market and investing in financial instruments that he clearly understood. That wasn’t what most people were doing.

You remember those pre-2008 days during the heyday of Wall Street, where people were swimming in champagne pools and things like that? Burry was one of the first people to predict that the whole industry was going to come crashing around 2007.

People hated him, of course. Who did he think he was to end the party?

Burry suffered an investor exodus and many worried he had lost his mind, demanding to withdraw their capital. Which he had to do, leaving him in a cash crunch that was stressful and frightening.

Eventually, Burry's analysis proved correct: He made a personal profit of $100 million and a profit for his remaining investors of more than $700 million.

Scion Capital ultimately recorded returns of 489.34% (net of fees and expenses) between its November 1, 2000 inception and June 2008. The S&P 500, widely regarded as the benchmark for the US market, returned just under 3%, including dividends over the same period.

What was this guy doing? He was avoiding groupthink, loathing being a follower and refusing to drink the Kool-Aid that hundreds of thousands of other people regretfully did. He was being creative, original and a contrarian, for all the right reasons, which were clear in front of his eyes.

Fun fact: Burry is portrayed by Christian Bale in the 2015 Oscar-nominated movie The Big Short.

How many times have you doubted yourself because your idea wasn’t the popular thing to do?

El Greco, Alfred C. Barnes and Michael Burry are just three names among the millions of people who have listened to their gut and trusted their instincts when they needed to rely on them. They are the definition of freethinkers and iconoclasts.

They didn’t want to fit in, they wanted to do what they thought was best for them and for the things they believed in. In the end, being a contrarian paid off.

Thank you for reading this far. Looking forward to hearing from you anytime.

There are no affiliate links in this email. Everything that I recommend is done freely.

THE CURATED GROOVE

A selection of interesting articles in business, art and creativity along with some other things worth mentioning:

3 common fallacies about creativity.

How creativity can boost your mental health

The best creative advice in 2021 according to entrepreneur magazine

Fascinating story about the Manhattan DA’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit

Collins Dictionary declares “NFT” the word of the year

Best art exhibition I saw in NYC last week