The Groove Issue 38 - Always Be Experimenting

Welcome to the 38th issue of The Groove.

If you are new to The Groove, read our intro here. If you want to read past issues, you can do so here.

If somebody forwarded you this email, please subscribe here, to get The Groove in your inbox every Tuesday.

ALWAYS BE EXPERIMENTING

Ralph Waldo Emerson used to say: “All life is an experiment. The more experiments you make, the better.” Breakthroughs in business and art always come from unconventional thinkers. Strange combinations that intrigue others and unusual solutions to problems - most often happen after periods of experimentation.

The opposite is also true: as people reach certain level of expertise, they start losing the desire for experimentation. It’s not uncommon for businesses and artists to use a tried-and-true formula that gives predictable results over and over again to the point that experimentation completely disappears. This is when complacency hits and irrelevance follows, regardless of how big a company or an artist is.

Running the Gamut

Victor Vasarely in his studio in Gordes, France, in 1978

Victor Vasarely was a Hungarian artist living in Paris working as a graphic designer in the 1940s. He couldn’t really come up with his own style and decided to embark upon relentless experiments. After all, he had a scientific mind; he had attended the University of Budapest’s School of Medicine before becoming an artist.

For decades, Vasarely tried everything fearlessly. In 1937, he created “Zebra” - what’s now considered the first Op Art painting. He was preoccupied with the idea of finding what would make his work engage and mesmerize his audience. He tried cubistic, futuristic, expressionistic, symbolistic, and surrealistic styles, without developing any trademark for himself.

But in the early 1950s, he started to find his own way. Vasarely thought: “I must include the viewer’s perception of the aesthetic experience; movement doesn’t rely on composition nor in a specific subject… but on the act of looking.” He focused his painting experiments on the optical effects of form and color.

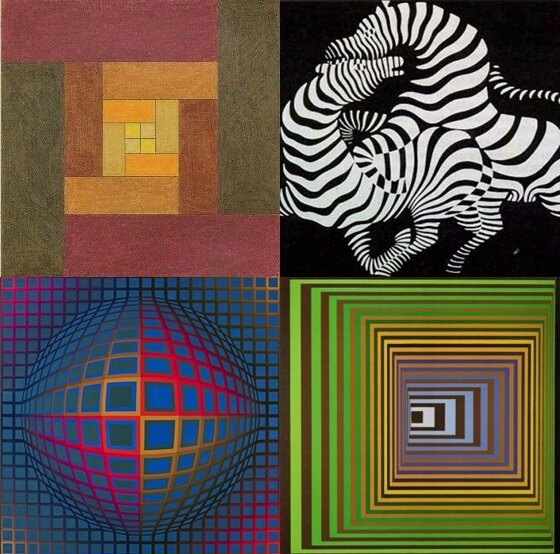

Some of Vasarely’s experiments from left clockwise: Etudes Bauhaus D, 1929, oil on board; Zebra, 1937, acrylic on canvas; Vega-Nor, 1969, oil on canvas; Vonal Stri, 1975, acrylic, canvas.

It wasn’t until the 1960s when Vasarely, unsatisfied with his monochromatic works, conceived something called the Alphabet Plastique, a grid-based system in which each letter of the alphabet corresponded to a specific color, geometrical form and musical notes.

This Alphabet Plastique and its endless permutations of geometric forms and colors landed Vasarely’s work in a 1965 exhibition called “The Responsive Eye” at MoMA where he was immediately dubbed the “Father of Op Art”.

The reaction of the public to Vasarely’s works in the exhibition was euphoric, because nobody had seen anything like his new works, which also meshed perfectly with the hallucinogenic vibe of the 60s. Even David Bowie became obsessed with Vasarely and in 1969 asked him to design the cover for his second album, Space Oddity.

From that point on and for the next few years, Op Art spread to advertising, packaging, fashion, and design. Vasarely’s fame and legacy was forever cemented in history.

Be on the Lookout for Happy Accidents

Halston with models and muses wearing Ultrasuede. Picture by Duane Michals, Vogue, December 1, 1972

Last week I finished watching the five episodes of “Halston,” the recently released Netflix series that captures the rise and fall of the iconic American designer Roy Halston. At the beginning, there’s a scene that shows Halston (played brilliantly by Ewan McGregor) talking to Elsa Peretti (played by Rebecca Dayan) and realizing with great surprise that the trench coat he designed with a new fabric called Ultrasuede wasn’t waterproof, but instead was completely drenched.

Given Halston’s surprise and since his shirtdress has been on the American fashion hall of fame for over four decades, I needed to investigate. Here’s the story: Halston first found out about Ultrasuede at a 1971 cocktail party in Paris when designer Issey Miyake, who was wearing an Ultrasuede shirt at the time, told him the material was “washable” — which Halston misunderstood as “water repellent.”

When Halston realized that his coat was an epic fail with waterproofing, he also had the epiphany that since it was made with a fabric that could be washed, it could become a revolutionary staple in women’s closets. And it was. A sexy and well-constructed dress that doesn’t have to be sent to the dry cleaner, whose material was extremely rare for clothes and shaped so brilliantly that it flattered everybody.

The knee-length Ultrasuede garment known as model No. 704 was introduced in the fall of 1972 and became as synonymous with Halston as the fabric it was made out of. It was priced at $185, which wasn’t cheap, but wasn’t insanely expensive. Halston sold 60,000 Ultrasuede dresses during that first season alone, and in the years that followed it became the dress that sold the most units in history.

After that, Halston kept using the same material in hundreds of other designs and capitalizing handsomely on them. Not bad for an experiment that turned into a happy accident.

Why not? / What if?

Think of all the things you do on a daily basis. Anything that you consistently need, or do, or engage with and have gotten used to, has potential for experimentation and improvement. Like inventive chefs in a kitchen who have to use new ingredients, mix salty and sweet flavors, hard and creamy textures, create experimental dishes, or add specials to their menus to keep delighting and surprising their customers, ask freely and without censorship about these two propositions: “Why not?” and “What if”?

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT

I have reopened enrollment in Jumpstart, my signature online course on creativity and business that contains the same step-by-step practical formula I used to come up with the ideas that allowed me to build a seven-figure business in the art world after quitting my miserable job as a corporate attorney 12 years ago.

You can trust that this blueprint, which unleashes an abundance of creativity in any form and is applicable to any profession or occupation, can also work for you, like it has worked for my past participants who are based in all five continents.

Some of their testimonials are available here.

The good news is that now you can join immediately. If you are ready to sign-up, all the information is here.

Generating original ideas in any profession or occupation, regardless of what you do, is the most valuable skill anyone can possess. Additionally, those ideas must materialize and come to fruition in a way that can create value for you and for others.

Jumpstart breaks down the process for you and helps you discover connections and associations you missed before, as well as how to spot trends and benefit from them before they become mainstream.

After years of teaching this program in person and then online, with hundreds of previous students reporting incredible breakthroughs that include opening new businesses, getting promotions, doubling and, in certain cases, even tripling their revenues, using the techniques that I teach you in the program, I now offer it to you with a new format.

The course is now completely self-paced, manageable on your own time, and always evergreen, as everything included in the program never expires.

You also get exclusive access to monthly, live Zoom Q&A sessions with me to discuss the doubts or questions you may have about bringing your ideas to life and capitalizing on them.

I’m hosting a Zoom webinar this coming Thursday, June 10th at 1:00 pm EST to go over what’s included in the new Jumpstart. Please register here if you want to know more.

And if you have any questions in the meantime, please feel free to email me at any time.

Thank you for reading this far. Looking forward to hearing from you anytime.

There are no affiliate links in this email. Everything that I recommend is done freely.

THE EXTRA GROOVE

Read:

Victor Vasarely. The Birth of Op Art Hardcover – by Márton Orosz and Gyorgyi Imre (Author)

Experimentation Works: The Surprising Power of Business Experiments by Stefan H. Thomke

Simply Halston: The Untold Story by Steven Gaines

Watch:

Victor Vasarely, a short video from CEAD

Vasarely: The artist as visual inventor, a video at the 2019 retrospective at Centre Pompidou

Ultrasuede: In Search of Halston. A documentary by Whitney Sudler-Smith