The Groove Issue 132 - Why Creative Success Is All About Realness

WHY CREATIVE SUCCESS IS ALL ABOUT REALNESS

There’s nothing more refreshing and ultimately creative than someone who is smart, has studied enough to support their ideas and fully owns and expresses who they are through their work.

How many people have been swimming upstream because instead of allowing others to inspire them, which is a normal part of developing one’s own ideas, they’ve decided to blatantly copy them and become someone they are not? The results usually speak for themselves, and not in the best way.

But if you look back at the remarkable career of Barkley L. Hendricks, you’ll notice that his uniqueness and success stemmed from the fact that he was well-studied, deeply informed about the past and present, and unapologetically himself.

Rely on a Strong Foundation

Barkley Hendricks in his studio in New London, Connecticut.

Creative self-expression is about showing your individuality, regardless of what you do. You could be making a painting or running the marketing department of a Fortune 500 company. The key is having such a strong foundation in the knowledge of what you do so that when you come up with your own thing, you rest on an unshakable level of confidence your critics can’t mess with.

While touring Europe as an undergraduate art student in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1969, Hendricks fell in love with the portrait style of artists like van Dyck and Velazquez. He went to visit the museums and churches of Britain, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands, but never saw a Black subject. He knew that filling this void would be a good way to showcase his ideas through his art.

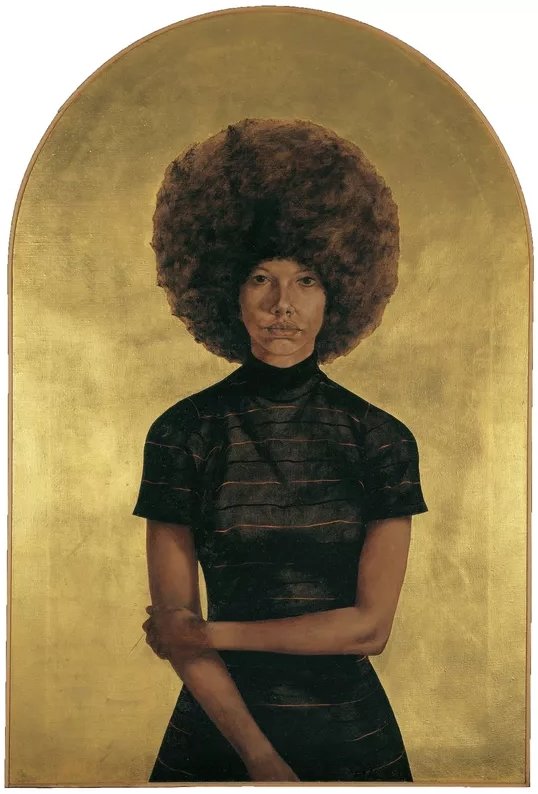

Upon his return to the United States, a 24-year-old Hendricks painted one of his most important portraits: “Lawdy Mama." This portrait of his young cousin sported an enormous Afro and looked impassively at the viewer. Although her dress was modern, the arched top of the canvas and background in gold leaf suggested a Byzantine icon.

This painting opened the door for what would become Hendricks’ signature style, unabashedly his but well-informed by art history and education: life-size portraits of friends, relatives and strangers encountered on the street that communicated a new assertiveness and pride among Black Americans.

Over and over, Hendricks explained that he never wanted to be political; he wanted to be himself. His arguments were always so well-crafted that he not only disarmed anyone who didn’t get what he was doing but also received support from galleries to show his work and from collectors who bought it.

Talent Isn’t Creativity

Barkley L. Hendricks, Lawdy Mama, 1969, oil and gold leaf on canvas

It’s one thing to have a talent, a special ability to perform a task, which Hendricks obviously had, given the flawless execution of his paintings. But being creative is a different matter. The latter is something that can be learned; the former is something that can be sharpened.

At Yale University for his MFA, Hendricks, who was also an avid photographer, spent more time hanging out with the photographers and not with the painting students. “There were only two representational or kind of upright-easel painters at Yale. And consequently the fellowship element was more with the photographers.”

This helped to sharpen what Hendricks called his “eyeteeth” so that his paintings wouldn’t be at all random or spontaneous but instead carefully thought renditions that relied on art history but also on marketing and advertising. “It's said you have maybe three to five seconds to get people's attention. Otherwise, they're off to something else. So I want to make sure that, you know, that three to five seconds at least I get your attention, then, as they say, you can't do anything with people if you don't get their attention.”

Based on these ideas, in the 1970s he produced a series of portraits of young Black men, usually placed against monochromatic backdrops, that captured their self-assurance and confident sense of style.

And in 1974, Hendricks painted “What's Going On”, one of his best-known portraits, named after Marvin Gaye's eponymous single. The blank white background on this painting and similar ones derive from popular standards of fashion photography, like Avedon and Irving Penn.

With the evolution of his work, Hendricks exemplified what British actor and comedian John Cleese once said: "creativity is not a talent, it's a way of operating".

Step Out of The Script

For something to be truly creative it has to tell a different story than what is out there. Hendricks knew this well. “There's nothing new out here. That's what irritates me about this culture - it always wants to play some dumbass game. I didn't care what was being done by other artists or what was happening around me. I was dealing with what I wanted to do. Period.”

He was motivated by the idea of creating “something that resonates with you first, rather than you trying to be connected with the unfortunate situation people of color face. There's a script that's been written, whether we like it or not. We're all a part of it. What needs to happen is for artists to get up and get out of that headlock scenario-out of that script that's been written that you had no control over.”

By 2008, Hendricks was a legend in his own right and his work was celebrated in a traveling retrospective aptly called “Birth of the Cool,” which started at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. It then traveled to the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Santa Monica Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.

Hendricks created his own visual language with his figurative paintings, which inspired other artists like Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas. When he died in 2017, The Atlantic wrote that “his paintings combined the tonality of Rembrandt with the sensibility of Andy Warhol,” all while challenging stereotypes.

The invitation and legacy of Hendricks is constantly reminding us that formulas and societal narratives of what things should be are nothing more than caps that restrict the flow of what we can do with our own authentic power.