The Groove 191 - How to Push Boundaries

HOW TO PUSH BOUNDARIES

People who push boundaries are the ones who leave lasting legacies. Their willingness to take risks, explore uncharted territories, and innovate drives societal progress and inspires others to think differently. By defying conventions and overcoming obstacles, these trailblazers open up new possibilities, whether through groundbreaking technological or scientific discoveries, revolutionary artistic expressions, or transformative social movements.

The art and artists that are remembered are those that transcend boundaries, offering profound insights into society, culture, and the human condition. Martin Wong profoundly exemplifies this power.

A forerunner to the identity-focused art movement of the 1990s, in which artists explored themes related to their personal and collective uniqueness, Martin Wong was born in Portland, Oregon in 1946 and grew up in San Francisco as the only child of a Chinese mother and Chinese-Mexican father. Understanding Wong's contributions at large provides us a compelling lens to appreciate how art can reflect and influence broader societal themes such as race, gender, sexuality, and cultural heritage.

Change Course… Smartly

Martin Wong, September 1992, in the Martin Wong Papers. Museum of the City of New York. Activity 26400, box 2, folder 33.

Changing courses while dedicating yourself to learning and studying can transform potential challenges into opportunities for success. By investing in your own education and skill development in each new direction you pursue, you equip yourself with the knowledge and expertise needed to excel.

Wong received a bachelor’s degree in ceramics from Humboldt State University in California, but he was also interested in drawing, painting and performance. “I made ceramics and did drawings at art fairs. I was known as the 'Human Instamatic.' It was US $7.50 for a portrait. My record was 27 fairs in one day. Friends said to me, 'If you're so good, why don't you go to New York?’”

And so he did. In 1978, Wong relocated to Manhattan, where he made his home in the Lower East Side and dedicated himself entirely to painting. Knowing enough about colors and pigments from his ceramics degree, Wong set out to capture the gritty essence of the decaying Lower East Side as a largely self-taught painter.

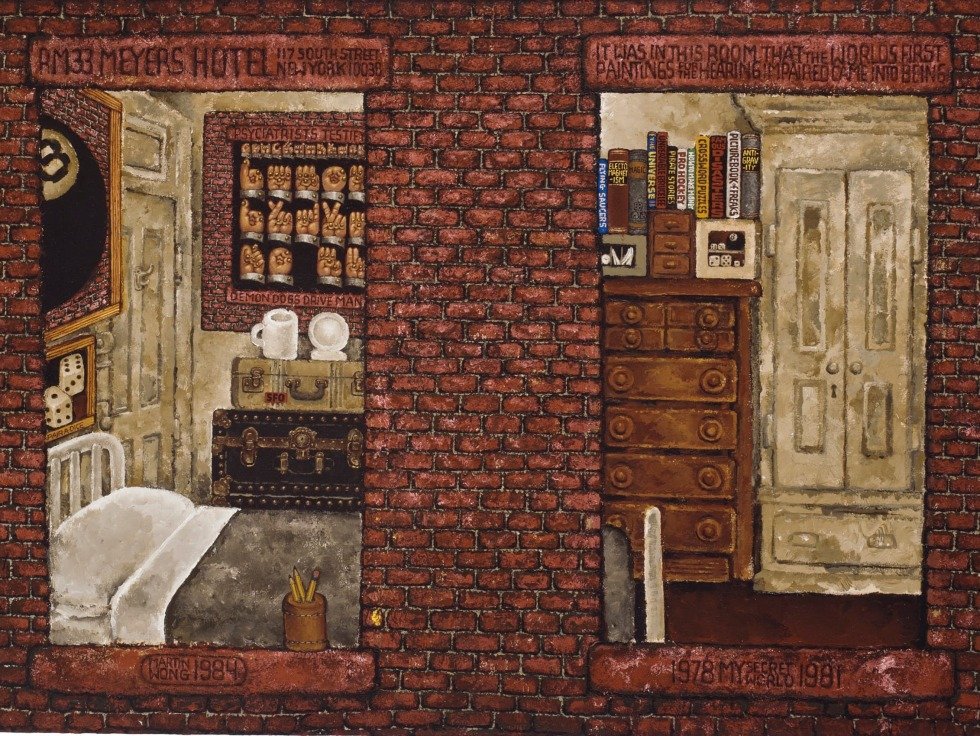

Martin Wong, My Secret World, 1978–81, 1984. Acrylic on canvas. (c) Martin Wong Foundation.

His paintings were both a reflection of and a reaction to the environments he inhabited: theatrical portrayals of the Lower East Side's dilapidated tenements and shuttered storefronts provided viewers with captivating blends of the ornamental and the realistic and the factual, the fantastical and the spiritual.

But Wong didn’t just translate what he knew, he studied and fervently visited galleries and museums and even worked at the bookstore of The Met Museum for a time. Through extensive self-directed study of artworks from a range of genres, Wong independently developed his artistic style, setting himself apart from contemporary trends. Several modern artists deeply influenced Wong's work, including Grandma Moses, Edward Hopper, Piet Mondrian, and Jasper Johns.

This commitment to continuous improvement ensures that you can adapt to new fields and stay ahead of industry trends. Moreover, it demonstrates resilience and a proactive approach, which are invaluable traits in any career. Ultimately, the combination of versatility and a strong learning ethic can turn any career pivot into a strategic move toward greater achievements. Nobody can push boundaries if they don’t know what those boundaries are.

Being Creative Means Stepping Outside

Martin Wong, The Babysitter, acrylic on canvas, in artist's found frame, 1988. (c) Martin Wong Foundation.

The job of the artist and of anyone else who wants to be creative requires engaging with diverse perspectives. This allows you to challenge stereotypes, break down barriers, and create work that resonates with a wider audience. This approach not only enriches your own experiences and skills, but also contributes to a more inclusive and empathetic society.

Wong gained prominence in the vibrant and often challenging environments of New York City's Lower East Side during the 1980s and 1990s. This period was marked by economic hardship, the AIDS epidemic, and significant social change. Wong's work emerged as a poignant commentary on these dynamics, encapsulating the lived experiences of the urban poor, LGBTQ+ individuals, and communities of color.

Pushing against Eurocentric expectations regarding suitable subjects for an Asian-American artist, Wong centered his artistic focus on Latino and African-American subjects during the 1980s, challenging prevailing theories of identity in the art world. These theories suggested that artists should restrict themselves to themes directly tied to their own ethnic and racial backgrounds. Wong couldn’t care less. He even learned Spanish to communicate better with his neighbors and gained the nickname of “el Chino Latino”.

In the subsequent decade, he shifted towards exploring his Chinese-American heritage, producing vibrant paintings that intertwined childhood reminiscences with lavish Hollywood interpretations of Asian culture. “It's weird because I can't speak Chinese but I paint Chinatown, it is almost like a tourist idea. It's just I remember more than say, an average tourist would, because I have the experience of growing up near there. My view of Chinatown is more like an outsider's view, whereas my view of the East Village, even though I'm not Puerto Rican, is more of my own view.”

Wong’s blend of Ashcan School realism, casual Pop Art charm, and folk-art enchantment made an alternate reality where the mundane becomes cherished and the mystical feels within reach. The outcome is an art that continues to resonate with a unique cultural era while transcending transient trends.

“Like I said, my main influence is probably social realist paintings from the thirties and forties that includes Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo.” Wong’s unique style made people look at his work with excitement and earned him countless exhibitions and numerous awards.

Embracing a broad range of influences and themes, like Wong did, encourages innovation and cross-cultural dialogue, ultimately leading to richer and more meaningful contributions in any field. His exploration of identities other than his highlights the importance of cultural representation. His work serves as a reminder of the vast number of experiences that make up society, and the value of preserving and honoring diverse cultural narratives.

Build a Bigger Legacy

Martin Wong, Polaris, 1987. Acrylic on canvas. (c) Martin Wong Foundation.

Pushing boundaries sometimes entails building a legacy outside of your main profession. That involves leveraging your passions and interests to create a lasting impact that others can enjoy and learn from. Begin by identifying causes or areas that resonate with you deeply, whether it's through community service, mentorship, writing, or collecting something.

Martin Wong's legacy extends beyond his artistic achievements. An enthusiastic participant in the street culture of New York City's Lower East Side, Wong emerged as the foremost supporter of American graffiti art. While living in New York, Wong built an extensive graffiti collection and, with the support of a Japanese investor, he co-founded the Museum of American Graffiti on Bond Street in the East Village in 1989.

At that time, graffiti was a highly controversial art form, and city authorities had removed much of it from the New York City subway system. Wong aimed to preserve what he saw as "the last great art movement of the twentieth century." In 1994, due to his declining health, Wong donated his graffiti collection to the Museum of the City of New York, which includes works by prominent 1980s New York graffiti artists such as Rammellzee, Keith Haring, Futura 2000, Lady Pink, and Lee Quiñones.

Not only did Wong leave an important legacy with his art akin to that of an investigative journalist showing us the urban decay, gentrification, and community resilience issues that remain relevant today, but with the collection that he assembled he aimed to show others what he saw: “when you look at the graffiti paintings, these are kids who actually grew up there and what they're painting, most of their imagery is outer space imagery. The spray coming from the can, it's like high technology. Their vision is actually closer to Japanese comic books than it is to social realism of the '30s. I don't think they're even that aware of it.”

When you are creative, you find the time and resources to invest into other pursuits, aiming to share knowledge, and to inspire and support others. Find like-minded individuals to amplify your efforts and ensure your initiatives have a broader reach. Document your journey and achievements, making them accessible for future generations to learn from and build upon. By committing to a meaningful purpose beyond your primary career, you can leave a multifaceted legacy that enriches the lives of many and fosters continuous learning and growth.

Martin Wong pushed boundaries and his contributions extend far beyond the confines of the art world. His ability to capture the essence of urban life, highlight marginalized voices, and explore complex themes of identity and culture make his work profoundly relevant to broader societal discussions. His legacy offers a powerful example of how art can serve as a mirror to society, reflecting its realities and inspiring change.