The Groove 178 - How to Expand Your Perspective

HOW TO EXPAND YOUR PERSPECTIVE

As humans, we’ve all had to witness extremists operating on their own, in legitimate governments and in marginal groups. Yes, there’s an expansive gray area that exists between protecting national and individual interests and the outright rejection of globalization, immigration and acceptance of other cultures. Yet in the last 10 years we’ve seen Brexit, horrific wars, the rise of far-right movements and an uncomfortable anti-immigrant sentiment that seems to permeate everything everywhere. How did we get here and how can we course-correct?

Last Saturday, I watched the Oscar-nominated Italian film “Io Capitano”, which chronicles the harrowing story of two Senegalese teenage boys who leave their homes in search of a better life. In their quest, they go through circumstances that most human beings couldn’t survive. I felt intense waves of anxiety, sadness, and empathy, thinking about what many of the people I see in New York, working as street vendors or delivery couriers, have had to endure just to live a life of dignity with basic human rights. This left me looking for an example of someone who melded all these worlds beautifully, and Pacita Abad crossed my mind.

Born in the small island of Batanes, Philippines in 1946, Abad is having her biggest moment 20 years after her passing: an enormously acclaimed traveling retrospective that began last year at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis which then went to SF MoMA in San Francisco. The show will arrive at MoMA PS1 in New York next month and culminate at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto next year. On top of that, Abad is one of the artists chosen for this April’s 60th Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, and aptly called “Foreigners Everywhere.” There are so many gems in Abad’s life and career that can be helpful to anyone who’s ready to expand their perspective:

Have the Will to Adapt

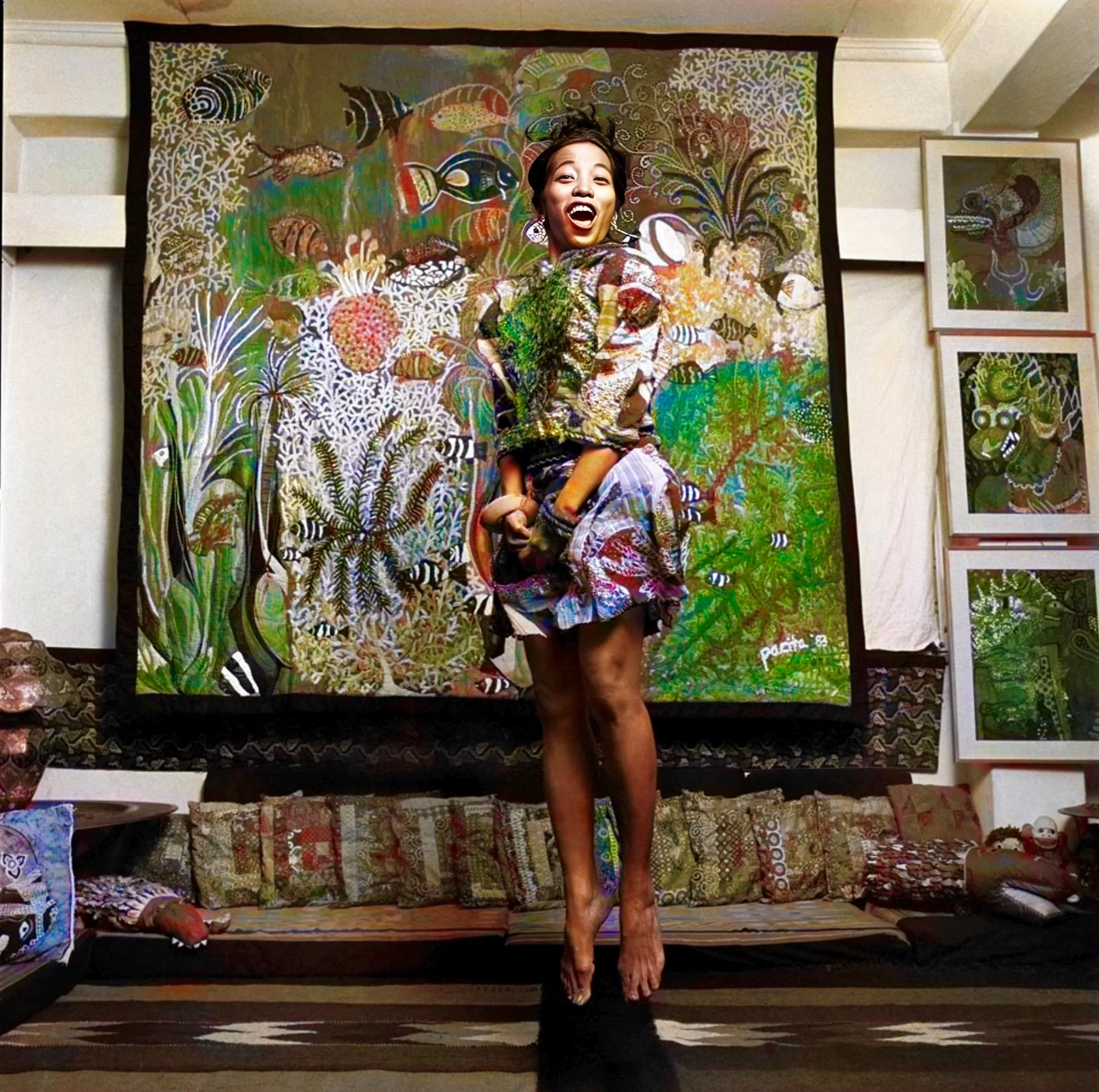

Pacita Abad photographed by Wig Tysmans in her Manila home in 1985.

Luckily, many of you will never have to leave your countries behind, but life is unpredictable and full of changes, bringing twists and turns that don’t necessarily involve moving places but require adaptability, resilience, and creative autonomy. While I understand that hardcore positions can be challenging to modify, I also think that, like George Bernard Shaw wrote: “those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything”. A lifetime of stagnation is a far more frightening place to be than having the disposition to reshape and widen your point of view.

Abad was forced to leave the Philippines in 1970 after the regime of President Ferdinand Marcos, who stole a congressional election from her father and threatened her life when she led student demonstrations in front of the presidential palace in Manila.

Landing in San Francisco with the idea of getting a law degree, Abad lived with distant relatives and worked two jobs to make ends meet. But by 1973 she had met and married the newly minted Stanford economist Jack Garrity and embarked on a yearlong trip across Asia with him.

Pacita Abad, Water of Life, 1981, oil on canvas.

Upon her return to the United States, she realized that she needed to become an artist, and in 1976 while living in Washington DC, she took up formal art training at the Corcoran School of Art. For the next 30 years, Abad and Garrity lived and spent time in 60 countries on six continents: Honolulu, Brisbane, Lima, Bamako, Rajasthan, New York, and Barcelona were some of the cities that she spent time in, while Dhaka, DC, Jakarta and Singapore were among the ones she called home.

Instead of being a source of discomfort or instability, this nomadic life nurtured Abad in more ways than one. Not only did she adapt well to each of these places, but she constantly strove to understand how people lived and ate, what they believed in and went through in their day-to-day lives.

Abad’s early paintings were figurative representations of the people she met along the way: refugees in Bangladesh, Tibetans seeking peace in Nepal, displaced Haitians working in infrahuman conditions in the Dominican Republic. Themes of migration, identity, and human rights frequently showed up in her work. By using her art as a platform for social commentary, she contributed to the broader discourse on art's role in addressing and challenging societal issues, and her commitment to social and political issues through her paintings reflects a sense of purpose: “I have always believed that an artist has a special obligation to remind society of its social responsibility.”

Her dedication to multiculturalism and exploration of diverse artistic styles showcased a global perspective. Abad's extensive travels and exposure to various cultures profoundly influenced her, contributing to the growing emphasis on cultural diversity and inclusivity in the art world. Her husband said it best: “She was much like a foreign correspondent in a way, telling people, this is what's happening in these places.”

Freedom With Rules

Pacita Abad’s trapuntos at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in Manila, 2018. Photo by Pioneer Studios.

Creative freedom in both art and business can thrive when supported by a framework of rules. Rules provide a structured environment that fosters innovation, protects essential values, and facilitates effective progress.

As an insatiably curious person, Abad felt that the flatness of her paintings was limiting so she began experimenting with stuffing and stitching her canvases in 1981. This gave birth to her famous “trapunto” paintings: “the term comes from the Italian trapungere, meaning ‘to embroider.’ I paint, using either oil or acrylic, on canvas and then collage. This top layer carries the design. To this I add a backing cloth and stuff polyester filling in between. The two layers are then joined with running stitches. The initial concept was inspired by a friend of mine, Barbara Newman, a doll maker who made life-size dolls.”

The trapuntos have been hanging from the ceiling of museums at Abad’s recent shows. The hand-stitches on the back of them are so neat and precise that the curators understood that both sides are an integral part of the whole. The artist was demonstrating that even the highest levels of freedom require rules.

“I have been inspired by looking at such traditional forms as the mola from Panama, huipil from Guatemala and Mexico, kalaga from Burma, embroidery from Afghanistan, tie-dye from Africa, and by the use of mirrors in India and shells in the Philippines and throughout the South Pacific. The technique that I have developed has very few constraints-it allows me to be spontaneous and innovative. I can incorporate many media and processes, including painting, stitching, collage, silkscreen, tie-dye and embroidery into a single work.”

When we see the meticulous process that she used in her work while appearing to be boundless and uninhibited, Abad was, in fact, laser-focused on the careful exhibition of neat craftsmanship that followed set rules.

The World Is Your Oyster

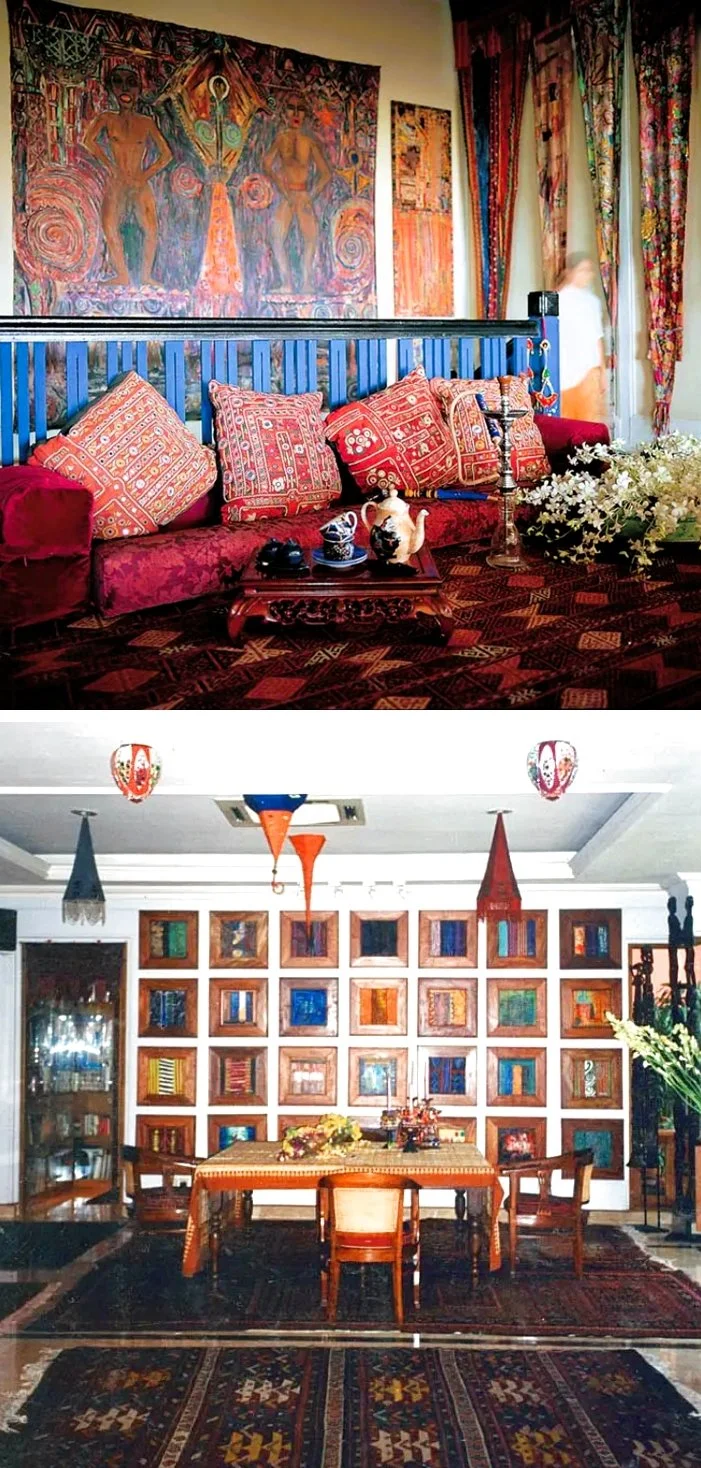

Pacita Abad’s home-studio in Singapore (top) and in Jakarta (bottom).

“The world is your oyster” is an empowering metaphor that encourages you to see the vast opportunities and possibilities awaiting them. Just as one opens an oyster to discover a precious pearl within, this saying suggests that the world holds limitless potential for exploration, growth, and achievement. It serves as a motivational reminder to embrace life with curiosity, courage, and a willingness to seize the opportunities that come your way.

Abad made more than 5,000 artworks in her three-decade career. She explored abstraction, figuration, masks, the natural world, cityscapes, and landscapes. She used glass, bark, paint, fabrics, beads, trinkets, paper, buttons, threads and pretty much anything that crossed her path and helped her express her ideas. She had the uncanny ability to make every place she went a fruitful experience, rich with inspiration that translated into her work.

I can only imagine that Pacita Abad was the most interesting guest at any dinner party. Because of her extensive travels she adorned herself with embroidered shawls, telling tales of Afghanistan's craftsmanship, the rhythmic clinking of beads and bangles from the lively streets of Rajasthan, printed scarves from the bazaars of Turkey, turquoise treasures from Iranian markets, a Shan bag from the heart of Burma and silver jewelry echoing the tales of Hill tribes in Thailand and Laos. She also turned her homes and studios into colorful mixes of tribal textiles and sculptures that played side-by-side with her art.

Abad taught us to cultivate our curiosity and to learn from diverse cultures, experiences, and perspectives. When you travel, either physically or through literature and media, you broaden your horizons and gain a deeper understanding of the world. When you build connections with people from different backgrounds, you foster rich perspectives. Be adaptable in the face of change, turning challenges into opportunities for growth. Ultimately, making the world your oyster involves approaching life with a sense of wonder, a thirst for knowledge, and the audacity to explore the vast and varied treasures it has to offer. This is the first step to a richer, more inclusive, creative, and accepting world.