Picasso Primitif

How does one write about a Picasso show without sounding cliché or repetitive? Is it possible to contribute anything else to the legacy of the most important, prolific and relevant artist of the past 100 years? I pondered these questions as I was invited by the Musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac in Paris to visit and experience their most important show in the almost eleven years since their opening in the summer of 2006: Picasso Primitif, a collaboration with the Musée Picasso and the first show ever to present Picasso’s work alongside indigenous pieces of non-western art.

The external glass wall of the museum. Picasso's portrait is by Herbert List.

A still from a video filmed at Trocadero Museum around the time when Picasso visited the first time in 1907. This same sculpture by African artist Akati Ekplekendo is physically present at Picasso Primitif.

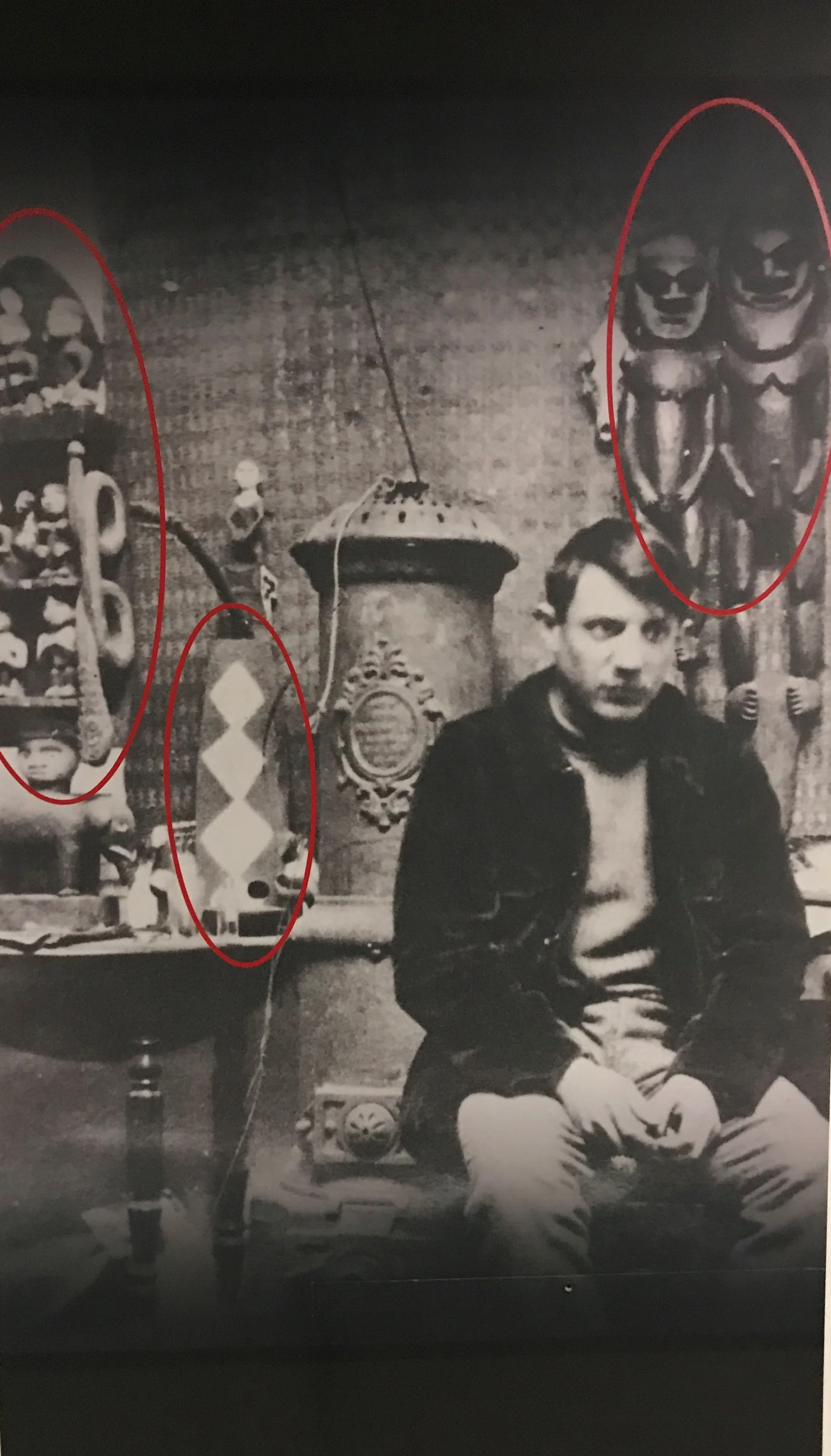

Picasso in his Bateu-Lavoir studio photographed by Frank Gelett Burgess in 1908.

Let's begin by saying that the Quai Branly is a unique institution: the youngest of the Parisian museums, the space, which is located on the 7th arrondisement in the left bank, was founded under Jacques Chirac's mandate (hence his name as a part of the museum's official title) with the purpose of highlighting indigenous art and the cultural and artistic conversations that have existed for millennia and continue to develop in the four continents outside of Europe. Encased by a long and tall glass wall that protects lush gardens which house more than 180 trees and 72,000 plants, the museum's exterior is red and its architecture is quite contemporary. The interior is dark and moody, in part for reasons of conservation, in part because the French architect Jean Nouvel designed it to give the visitors a sense of mystery, evocative of remote places. The permanent collection, with more than 300,000 objects, sculptures, figurines and other pieces from America, Asia, Oceania and Africa, is impressive to say the least (and this number doesn't include the numerous musical instruments, textiles, photographs and paintings that are also property of the Quai Branly), and at any given time only around 3,500 are in display. To have a greater understanding of the museum and its mission, I welcomed a refresher walkthrough of the permanent collections (which are organized by continent) with the Deputy Director of Collections and Heritage Department, Emmanuel Kasarherou. A reminder that many of these objects were used for initiation rituals and are believed to carry magical powers helped me appreciate even more what I was to see the next day at the Picasso show.

Olga Khokhlova at home. Anonymous photograph blown up in the chronology section of the exhibition.

With Cubism and the incorporation of ethnic and non-western art elements in his paintings, sculptures, ceramics, etchings and more, Picasso developed aesthetic canons that after him have been embraced and used by many generations of artists. Picasso Primitif, curated by Yves Le Fur, Director of Collections and Heritage Department of the museum, looks above and beyond the issue of "influence" that these objects had in Picasso's work. For Picasso, ethnic art was not considered a source of formal elements that he could have acknowledged as artistic influences in his work. Instead, it was a passion, a fascination, and as such, he bought, sold, traded and received as gifts many of these objects throughout his life.

Hélène Fulgence, Director of Exhibitions, guided me through the show, which is split into a chronological section and an exhibition where 107 Picasso works that range from large oil-on-canvas paintings to etchings to assemblages and bronze sculptures are displayed and interspersed by objects like Inca terracotta pottery from the 1400s, African wood carvings from the 1800s, and Vanuatu masks made of natural fibers from the beginning of the 20th century.

The chronology section starts in 1900 when Picasso visited Paris to display one of his paintings in the Andalusian pavilion of the Exposition Universelle, highlighting with a map of the exhibition that the space was located near the Senegal, Sudan, Tunisia and Cote d’Ivoire’s pavilions. Two things happened in that trip: 19-year-old Picasso fell in love with Paris and possibly had a chance to see up close the work of African artists that were participating in the Exposition Universelle as well. However, it wasn’t until 1907, when Picasso was already living in Paris, that a visit to the Ethnographic Museum of Trocadero (now Musee de L'Homme) sparked Picasso's long-life interest in collecting and living with tribal artifacts, masks and sculptures that then appeared reinvented in his fragmentary compositions, perhaps as an intuitive reaction to the end of European imperialism, as a search for emotional visual language that connects humans to our most primitive parts and as a nod to the existence of other cultures. That same year he also bought his first non-western sculpture: A Tiki wood figure from the Marquesas Islands dating from the 19th century and which is displayed in the show in front of a reproduction of one of Picasso’s most important works: Les Demoiselles D’Avignon. The impression that the visit to the Trocadero Museum created in Picasso made him rework Les Demoiselles, trading the faces of the two prostitutes on the right of the canvas for African masks. This innovative approach was also made out of a decision to generate a connection with the primitive, and perhaps also out of fear of these women, that they may have gotten him sick, or that he may have fallen for one of them.

A reproduction of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon with the original Tiki sculpture that Picasso first bought for himself in 1910.

Many photographs of Picasso in his studio in Cannes taken by relevant photographers of the 1950s and 1960s like Mark Shaw, Edward Quinn and Lee Miller are shown in the chronology, illustrating how throughout Picasso’s life, he was surrounding by these precious objects that accompanied him in his studio and homes until his death in 1974.

Picasso and Brigitte Bardot photographed by Jerome Brierre in 1956 at Picasso's studio in Cannes.

Picasso in his studio of La Californie, in Cannes photographed by Edward Quinn in 1959.

Picasso was so intrigued, moved and fascinated by these objects, that he told Françoise Gilot, his partner for more than ten years and the mother of two of his children, who wrote in her 1964 book, Vivre Avec Picasso, that: “the African masks were not simply sculptures like any other. Not at all. They were magic objects…They were weapons. To help people stop being ruled by spirits, to free themselves. Tools. If we give a form to these spirits, we become free…I understood why I became a painter…Les Demoiselles d’Avignon must have come to me that very day, when I visited the museum and saw the African masks, but not at all because of the forms; because it was my first exorcism painting”. What Picasso was saying is that art changes people, it transforms the artist, it has power over the viewer, it is no longer about depicting nature or the human body - it is a point in art history that begins a new era and a reinvented way of making art.

The exhibition portion of the show is divided in three major areas: Archetypes, Metamorphoses and “Id” (as in the Freudian concept that explains the impulsive, unconscious and intuitive part of human beings).

Pablo Picasso's oil-on-canvas, Jeune Garçon Nu, 1906 surrounded by sculptures from Polynesia, Iraq, Nigeria, Indonesia and Vanuatu.

The Archetypes area, with the body and its geometry at its center includes nudity, stylization-verticality, the symbolism of the body through lines and bodies in relief and counter-relief. It was interesting to see many anonymous African sculptures next to Picasso’s and not being able to tell who did what. Stylized, elongated figures made of wood stand next to each other proving a concept in the interest of artists to recreate the body in that particular way. A 1908 Picasso drawing in gouache and pastel that deconstructs the figure is displayed next to a 19th century wood statue from Gabon, whose twisted legs and geometrical proportions could have been made at the same time by a Cubist artist. A series of 11 crayon-on-paper drawings from 1946 show Picasso’s unique and decidedly Cubist take on the line and the body in an unpretentious way. These rare drawings, entitled Nu Debout (Standing Nude), are almost never shown because of their fragility.

The sculpture on the left is Pablo Picasso's Buste de Femme (Fernande), 1906 the other ones to the right are by anonymous African artists.

Pablo Picasso's Nu Debout drawing series from 1946.

The Metamorphoses section deals with the use of materials and found objects transformed into something else, like when Picasso made assemblages and sculptures in the exhibition’s “Woman with Stroller” 1950, whose face was created out of a stove, the body out of the plates of an oven and the breasts out of cake molds. It is brilliantly juxtaposed with the sculpture by African artist Akati Ekplekendo, whose “Sculpture Dedicated to Gou” 1858, made with machetes, chains and musical instruments, does not hint at a creation 100 years apart and with more than 4000 kilometers of geographic distance between them. Other many examples of Picasso’s and of non-western works range from reversibility (masks and shields created in New Guinea in the 20th century use the technique as often as Picasso, reversing an image to create an illusion of a double face) to "mise en abyme" like Picasso’s Grande Nature Morte au Gueridon 1931, which is both a female body (inspired by the pregnant Marie-Thérèse Walter) and also a still life where arabesques and curves repeat along with a grid and diagonal lines and displayed side-by-side an 1800s ceremonial Chilkat cape woven by the native peoples of British Columbia, Canada that is inlaid with repeating motifs similar to a totemic structure.

Akati Ekplekendo, Sculpture Dedicated to Gou, 1858

Pablo Picasso, Woman with Stroller, 1950

1800s ceremonial Chilkat cape next to Pablo Picasso's Grande Nature Morte au Gueridon, 1931.

Somali wall decorative piece, 1933

Pablo Picasso, Buste de Femme, 1943

The most intimate and complex part of the show is “Id” and this is where the instinct, the primitive urges that Picasso had all his life, are presented and explored. Picasso disfigured faces, changed his subjects’ expressions and painted intent, big eyes and twisted bodies as if they were magic. The faces he painted in his canvases, in terracotta vases and in drawings, are compared to those made by the Incas in the 1400s and 1500s, anthropomorphic wood masks from New Guinea, and Ethiopian ink-on-parchment figures whose eyes are the focal point, where the hollows seem to both seduce and scare. Disfigurement is also one of the revisited themes; as Picasso displayed hundreds of times in his portraits: by disrupting the symmetry of the face, there is no other choice but to confront the inner character of the subject. In this area of the exhibition there are several small-to-medium size Cubist portraits that Picasso executed on canvases and wood boards, such as La Femme Qui Pleure, 1937, whose sadness is so palpable that the disfigurement is not a distraction to her feelings. This plasticity of the human body has also been explored extensively in non-western art - the Mexican figurines made of painted plaster in the early part of the 20th Century, or the Congolese Kifwebe wood mask from the 1960s where all natural proportions have been altered mostly with the intent to turn such objects into magical or ritual pieces with powers beyond their own existence.

Pablo Picasso, Masque, 1919, is the second from the left, surrounded by African and Indonesian masks from the 20th Century.

Pablo Picasso, Tête d'homme Barbu, 1979, Mexican Mask from the 20th Century and Pablo Picasso, Carreau Industriel Dècorè au Verso d'une Tête de Faune, 1961.

Pablo Picasso, Mère et Enfant, 1907.

Pablo Picasso's portraits in the exhibition's "Id" section.

Pablo Picasso, La Femme Qui Pleure, 1937

Sex was always a big theme in Picasso’s life and in his work, so as an impulse, which he had no desire to control, this is an important area to understand the impetus behind what he made. As a side note, Picasso watched a lot of porn in Paris in the 1950s and 1960s, he said with the intent to understand the objectification of subjects. Many pieces stemmed from this era, including a tiny ceramic sculpture, Femme Nue Debut, 1950, which is said to have been inspired by the all the peep show visits to Pigalle. Lovemaking between a woman, who almost always is one of Picasso’s lovers or wives, and a man, who is Picasso symbolized as a mythological creature or simply as a “painter” with his model, were recurrent in his ouvre. A 1967 drawing, which is rarely shown, depicts a raw close-up of a penis-vagina penetration, which I wouldn’t call “shocking” but is nonetheless quite graphic, figurative and not Cubist. A group of etchings from 1966-1968 show a series of more primitive-style disembodied penises that play humorously with other figures of men and women drawn inside the phallic shapes. These are subject matters that non-western artists also dealt with constantly, as a variety of wood, basalt, terracotta, stone sculptures and figurines from Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, New Guinea and several other countries are placed around Picasso’s erotic work, showing male figures with exaggerated erect penises, phallic objects, and monolithic carvings.

Pablo Picasso, Femme Nue Debut, 1950

Pablo Picasso, Sans Titre, 1967

Pablo Picasso, Le Peintre et son Modèle, 1964; Pablo Picasso, Le Peintre et son Modèle, 1967 and a New Guinea wood lintel from the beginning of the 20th Century above.

Anonymous African statues from the 20th century

Pablo Picasso, Scène Erotique, 1902.

The ethos of Picasso Primitif is about the human condition. The unknown artists whose works are shown next to Picasso’s were in many instances hundreds of years before his existence, yet they were exploring the same psychological and emotional issues: love, instinct, sex, desire, emotions and that irrepressible, innate urge to create art. Like the phrase Picasso told Christian Zervos, the founder of Cahiers d’Art: “how can one penetrate my dreams, my instincts, my desires, my thoughts, which have taken a long time to elaborate themselves and bring themselves to light, above all seize in them what I brought about, perhaps against my will?”

Picasso Primitif

Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac

7 Quai Branly, 75007 Paris, France

Until July 23rd, 2017

*Bonus: if visiting Quai Branly, the restaurant on the rooftop, Les Ombres, is absolutely stunning. Everything in the restaurant has been designed by Jean Nouvel, and the food by chef Frédéric Claudel is magnificent. It doesn’t hurt that it has one of the most spectacular panoramic views of Paris, including an incredible proximity to the Tour Eiffel.

Also, on the mezzanine of the museum, the exhibition L’Afrique des Routes, curated by Gaëlle Beaujean, Head of Africa Collections, who graciously walked me through it, puts in a very special way the history of Africa and how the routes by river, land and sea brought to the west materials, artworks, syncretic movements, religious influences, maps, fabrics, objects and more that have had a direct contribution in the cultural developments of the western hemisphere. Works dating from the fifth millennium include chariots engraved in caves in Oued Djerat in the Sahara to the Chinese porcelain of Madagascar and are shown along with pieces from contemporary artists like William Kentridge and Yinka Shonibare.