Of Biennials and Controversies

I visited the Whitney Biennial during two separate previews the week of the 13th, and while I wish there had been less visitors and journalists and TV cameras, I saw what I was primarily interested in seeing: visually compelling work that has depth and grit, humor and pain. Work that is engaging and interesting from every angle, that's political and critical and tries to tackle the issues we are living right now with honesty and compassion. I was very happy to see many of the artists proudly standing near their works and felt that for the first time in years, the Biennial was on to something.

This year, the Whitney Biennial moved me. Maybe it was the combination of the new building and the young curators, Mia Lock and Christopher Lew, who did a great job in selecting a good balance of emerging talent and more established names that resulted in a particularly special combination of artists who truly have their finger on the pulse of events and are innovating and reinventing art using their own visual vocabulary. The exhibition gives the feeling of community, of artists coming together stronger than if they were exhibiting alone.

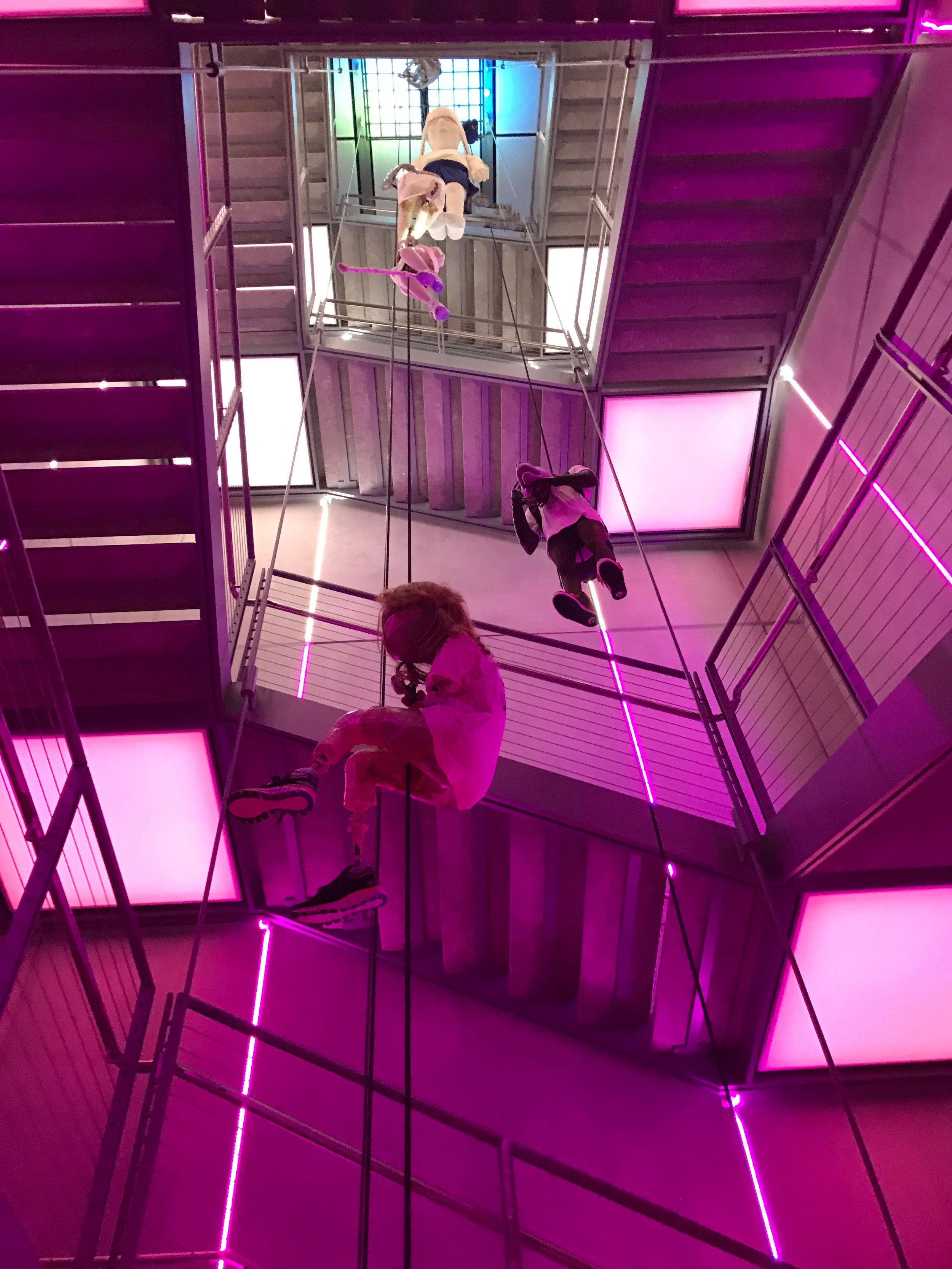

Raul de Nieves, Beginning & the end, neither and the otherwise, betwixt & between, the end is the beginning, 2017

Among my favorite installations were:

Ajay Kurian's "Childermass." Staggered in the main staircase bathed in pink light like sci-fi characters, people-like sculptures reminiscent of pole dancers or circus acrobats with masks and creepy faces culminate with a chameleon whose tyrannical demeanor and changing behavior seems eerily similar to the political leaders in this country.

Raul de Nieves's who made a stained-glass wall installation covering six large windows on the 5th floor that mimics those at churches with simple materials like glue, paper, acetate sheets and carton cut-outs with the words "Peace, Love, Hope, Truth, Harmony, Justice." Raul’s work deals with metaphors: everything has a deeper meaning - the words, the symbolism, the religious tone. There's always the possibility of something spectacular coming from despair. The installation is also a way for him to deal with fear; fear of uncertainty, failure or the unknown, but also as a way to show that deeper values can get us through the anxiety of our times.

One of Carrie Moyer's acrylic painting with one of Jessi Reaves's sculptural chairs

Carrie Moyer's large, saturated, magnetic, seductive, acrylic abstract paintings full of glitter are evocative of curves and female sexuality in a complex but approachable way, giving the audience visual stimulation and an idea of depth.

Aliza Nisenbaum (who was born in Mexico but is now based in Brooklyn), whose paintings show the reality of immigrant's lives in the United States.

Samara Golden tackles social and economic disparity with a fantastic installation right by the windows facing the Hudson river. Through small-scale maquettes that are then amplified with mirrors, Golden makes a space that looks like an expensive Manhattan condo adjoined with a cluttered office and an institutional space that is part hospital and part prison. Pretty much like real life in New York City.

Samara Golden, The Meat Grinder's Iron Clothes, 2017

I liked many more installations, in fact way more than what I could possibly write here. However, two pieces have been on my mind for "controversial" reasons and they were the ones that prompted the writing of this entire post.

Before writing about those two works, going back historically and briefly analyzing why the Whitney Biennial is so relevant, or at least the ethos of it, is because it is supposed to be looking at the art and artists that are truly expressing the current moment. The curators focus on the content and subject matter and sometimes on the techniques used by some of the artists, some of them very novel (like virtual reality on 3D glasses), and some of them taking a fresh approach on traditional ones like painting or sculpture. Whitney Biennials have not been without controversy, because, well, in part that's the point: to bring the unruly out, the unusual, the one that is saying what others don't. And that means that there will be some feathers ruffled, some people will be uncomfortable, others will feel not only entitled to their opinions but also absolutely right about them - the Whitney Biennial will always trigger lots of reactions.

Aliza Nisenbaum, MOIA's NYC Women's Cabinet, 2016

So it was in 1985, when some critics and journalists dubbed that Biennial, which focused on the artists of the East Village, as "the worst ever." Artists like Kenny Scharf, Tom Otterness, Eric Fishl, Elizabeth Murray and Alice Neel were labeled as decorative, selfish and childish. History has proved these critics wrong.

In 1987, and horrifyingly also in 2014, the number of women artists chosen to be in the Biennial was very dismal. The critics and the public bashed both editions for that reason.

The 1991 Biennial reflected the AIDS epidemics and showed lots of sexual, violent and political scenes that were called "devoid of any artistic value" but only considering the historical moment. Kiki Smith, Mike Kelley, Jasper Johns, Cindy Sherman, Julian Schnabel and Roy Lichtenstein were among the artists in that biennial who encountered severe criticism from both the press and the viewers

This year is not extremely political, although many of the current issues we are experiencing daily in this country, including the state of politics, the economic uncertainty, immigration, police brutality, gender matters and racial tension, are openly and bravely addressed by the artists. There are two pieces in particular that kept me thinking even two weeks after the previews - “Debtfair” by Occupy Museums and "Open Casket" by Danna Schutz. These two works especially had me pondering of the dangers that extreme, polarized opinions bring to society and to art.

Occupy Museums, Debtfair, 2017

Occupy Museums, presented Debtfair, a very well executed piece: an entire wall cut open in the form of an infographic, with an upward zig-zag line showing the ever-increasing profits of financial behemoth BlackRock. Inside the carved "profit" area there were smaller works embedded on the wall: photographs, assemblages and paintings, by other artists whose financial situation has been affected by having acquired debt. So far, everything is, in my opinion, interesting and smart except I'm not sure why BlackRock is the target of Occupy Museums. When I looked up, I saw written on the top of the carved wall, that the target is more than BlackRock, it is Larry Fink, it's CEO and founder. Furthermore, the caption and legend on the wall, states in part that "Debt Markets produce lucrative profits for wealthy individuals, who make up the majority of museum board members and the museum class. Here the relationship is embodied in the figure of Larry Fink, a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art and the CEO of mega-asset-management company BlackRock (which trades on every debt represented on the wall)." Seriously? This is where I realized that the argument supporting Debtfair, was not well developed or sufficiently researched and somehow dangerous to the general public, the binary system of always wanting to portray Wall Street as the enemy is perpetrating division and instigating hatred unnecessarily.

Occupy Museums, Debtfair, 2017

I'm not an ass kisser of Wall Street and have criticized the industry when the criticism is warranted, but that doesn't mean that everyone in the financial industry is a crook and out to get artists and other creative people "just because." I don't know Larry Fink personally, but I know people who work for him. I have heard and read about him and BlackRock many, many times for the sole reason that I have lived in New York City for seventeen years of my life and this is a place where the economy is primarily fueled by Wall Street and financial services. Now, I'm in no position to take the bullet for Fink, but I also can't accept vague accusations that manipulate the viewers incorrectly. If the debt that affects these artists comes from student loans, that hot potato has been rolling and passed from administration to administration since the 1950s. If it is another type of debt, we would have to figure out why so many artists incurred such loans. What if we change the argument? What if the debtors knew what they were getting into and left things to chance? Is that possible?

Fink, an ordinary guy born in LA, grew up in a middle-class family and moved to New York in 1976 to work in Wall Street with no privilege, no trust fund, no pedigree, no royal last name - just a lot of ambition and the willingness to learn and succeed. After having a very successful career with different banks, he founded BlackRock in 1993 and has been laser-focused for the past 24 years in growing his own business - today he employs 12,000 people. I doubt that those 12,000 people are all billionaires in Ferraris, but let the Occupy Museums people run with magical thinking and maybe 12,000 can be made billionaires overnight and that will help us all. And yes, being a trustee of the MoMA is probably costing Fink several million dollars every year because he is, most likely, very passionate about art (the tax write-off alone isn't enough motivation for these guys), and yes, his contribution is massively important because without him and all the other very, very wealthy patrons of the arts, we would not have the first class museums and cultural institutions that we have in New York City. We already know Federal and State funding and ticket fees and merchandise in museum shops will not pay for the staff, maintenance and the exhibitions and programming and performances that we are used to. Larry Fink and his patron friends are very much needed, in fact, welcomed, in the museum and arts realm, whether they are trading debt, equities, influences or coffee.

To have such tunnel vision (all Wall Street is bad, everyone else is good), is the very same reason why we seem to have fallen into one of the deepest holes in political history that this country has ever seen. Being radical to one extreme or the other doesn't advance anything, and lack of perspective can be deadly. I have to quote Jamie Dimon (CEO of JP Morgan and another demonized Wall Street exec) who gave a great interview to Bloomberg Magazine in December of 2016, "145 million people work in America; 125 million of them work for private enterprise; 20 million work for government—firemen, sanitation, police, teachers. We hold them in very high regard. But you know, if you didn’t have the 125, you couldn’t pay for the other 20. Business is a huge positive element in society. But for years it’s been beaten down as if we’re terrible people."

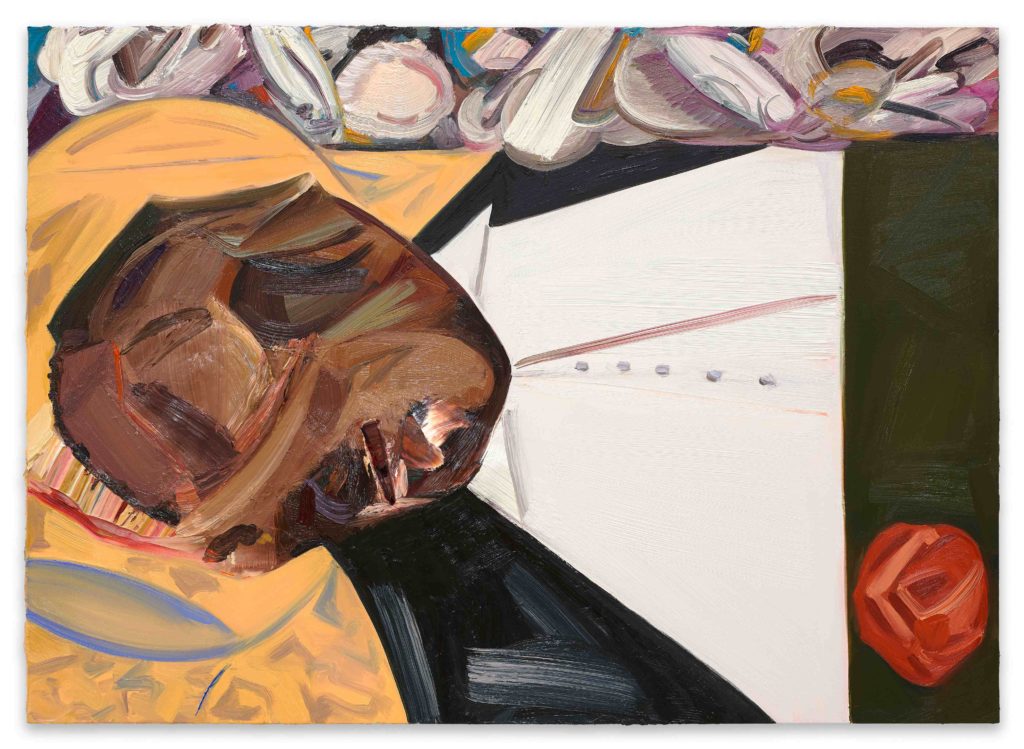

Danna Schutz, Open Casket, 2016

Dana Schutz is a fantastic artist who blurs the figure and the object; she always finds the perfect spot between figuration and abstraction. I've been a fan of her work for many, many years although I don't know her personally. The colors, the humor, the composition - all those faces and characters share one canvas with such energy and power. Dana painted three pieces for the Biennial; one of them is “Open Casket.” During the previews, nobody went berserk for "Open Casket," or if they did, they kept it to themselves. But when the Biennial opened to the public on Friday the 17th, all hell broke loose because of this piece. The medium-size painting shows the blurry face of Emmet Till, a young African American man from Chicago who was lynched, marred and tortured in Mississippi in 1955 at the age of 14 for erroneously being accused of flirting and whistling to white women. His mother wanted the disfigured face of the boy to be shown in an open casket so everyone would see the monstrosity the teenager had been a victim of.

Parker Bright, an artist, arrived at the Biennial this past Saturday and stood in front of “Open Casket” and said that he was peacefully protesting and nobody should see the painting because according to him, it was a “Black Death Spectacle” - words that he also wrote with a sharpie on the back of his t-shirt. Shortly thereafter, artist and writer Hannah Black, who lives in Berlin, posted a long letter on Facebook demanding that the painting be taken down and destroyed, she asked other artists who felt as offended as she was to co-sign the letter with her. (The letter has since been deleted). She emphasized many times how non-blacks can’t ever feel the pain of being black and went as far as to suggest that the painting was made for fun and for Schutz's profit. Then somebody sent a letter to the Huffington Post pretending to be Schutz herself, apologizing for creating “Open Casket.” The letter was, of course, a hoax.

Now, “Open Casket” isn’t going to be taken down and Schutz very briefly addressed the issue by saying that while she isn’t black, she is a mother, and I must add, a human. The painting isn’t for sale, and how can Dana Schutz - an artist with over fifteen years of career, with several solo shows in some of the most respected museums in the world, whose paintings have a waitlist for collectors through her primary galleries and whose secondary market prices at auction can go above $300,000 - going to profit from “Open Casket”? How polarized must people be to find artists censoring artists because of the color of their skin? To be an artist is precisely to have the freedom of expression to create whatever is in the artist’s mind or heart, especially when it is done with compassion, like in Schutz's case. Why are creative people erecting so many barriers, particularly since we all feel that the current state of affairs is already imposing barriers on us. Like Kara Walker (who was Dana Schutz’s professor), wrote in a brilliant Instagram post: we are so much more than the color of our skins, or the trauma that we have lived, or the sum of our experiences.

The painting will outlive the controversies and my deepest wish is that any future controversies be based on points other than questioning an artist's sense of humanity, or doubting that an artist can feel empathy or sympathy for other human being’s circumstances. If artists are to be denied this privilege, if censorship and “politically correct” paintings are to be the norm, we might as well just let conservatives and extreme-right leaders run this game and decide who can paint what and where to show it, what industries must be demonized and its people persecuted and publicly scorned, and who should always be right and who should be penalized if deviated.