The Groove 184 - Why You Should Unlearn to Become More Creative

WHY YOU SHOULD UNLEARN to become more creative

Life is consistent learning but also, paradoxically, unlearning. While I have advocated and written for years about looking at the lives of artists and their works for lessons to increase your creativity and find unusual solutions and surprising answers to common questions, it’s also crucial to forget rules, paradigms and programs that block our intuition and condition our way of thinking. This is perhaps the hardest thing to do.

It's generally estimated that our conscious mind can process around 40 bits of information per second, while the subconscious mind can handle a significantly larger amount, potentially in the range of millions of bits per second. All our education and lessons from media and experiences that we have lived since the day we were born are stored in our subconscious. How do we unlearn what has been so deeply ingrained?

Jean Dubuffet is an extraordinary example of someone who did just that. Born in Le Havre, France in 1901, he entered the Parisian and New York art worlds when he was in his 40s with his unconventional approach to creativity and his rejection of traditional artistic norms. His ways of thinking and attitudes offer great lessons that can be applied beyond the realm of art.

Seek the Unconventional

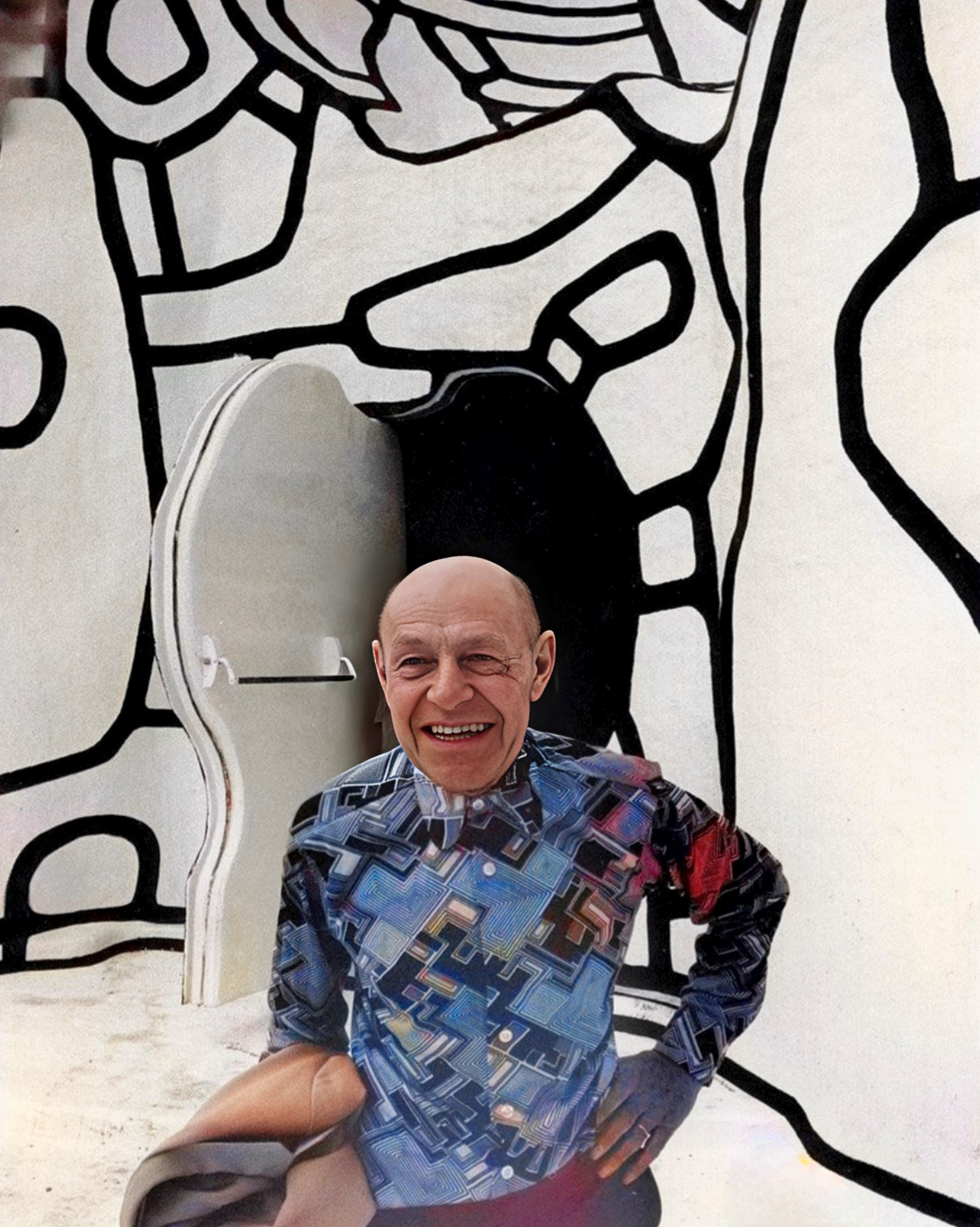

Jean Dubuffet at his Closerie Falbala in 1973. Photo by Kurt Wyss.

If you actively seek out unconventional sources of inspiration and explore beyond the boundaries of what has been given to you, you can retrain your mind into a process of cognitive restructuring.

For Dubuffet this was second nature. While he attended the respected Académie Julian in Paris, he dropped out after six months to paint on his own, and six years later gave up painting completely to run his father’s wine business. But an artist always goes back to making art, and in 1944 at the age of 41, Jean Dubuffet had his first solo show in Paris, where he showed oil paintings applied with impasto techniques, enhanced by materials like sand, tar, and straw, yielding distinctive textured surfaces and motivated by the common things. “I became convinced that artistic creation had to be anchored in everyday life.”

By 1946, he was already showing in New York at the gallery of the largely influential Pierre Matisse (Henri Matisse’s son), and around the same time he started researching and collecting art made by people with disabilities, prisoners, and children. Work made by outsiders to the establishment fascinated Dubuffet and became his most important source of inspiration. He coined the term Art Brut, or "raw art," to encapsulate work generated by aesthetics diverging from the rigid ideals of artistic genius upheld by high modernism.

Jean Dubuffet, Bédouin sur l’âne (Bedouin on a donkey), 1948. Oil and mixed media on canvas laid down on board.

Dubuffet challenged prevailing notions of what constituted art. This willingness can benefit anyone in any career. For example, Dominique Crenn, the first and only female chef to have been awarded 3 Michelin stars in the US in her San Francisco restaurant, Atelier Crenn, never went to culinary school. Crenn is renowned for her avant-garde approach to cooking, rooted in her background in literature and poetry.

Consistently looking for unconventional sources of inspiration requires a desire to explore beyond your immediate field of expertise. Embrace diverse perspectives, engage with different industries, and seek out new experiences that challenge your assumptions and expand your horizons. You’ll be thrilled by what you can find.

Reject Institutional Pressures

Jean Dubuffet, Rue de l’Entourloupe, 1963. Oil on canvas.

I know this one can be so difficult. We have been given so many rules and regulations and are fed stories that are not relevant anymore, or worse, not even true. It’s not that every institution should be distrusted, it's that each institution should be scrutinized, especially if they have been dictating how to do things for too long.

Dubuffet believed that art should reflect genuine human experience rather than adhere to commercial or institutional pressures. By staying true to his own vision, he garnered respect and admiration from both peers and critics alike. This commitment to authenticity serves as a reminder to stay grounded in your values and principles, more so in the face of external pressures.

Even the traditional concepts of beauty entrenched in art history were repulsive to Dubuffet: “I consider the western notion of beauty completely erroneous. I absolutely refuse to accept the idea that there are ugly people and ugly objects. Such an idea strikes me as stifling and revolting.”

To elegantly challenge institutions and the establishment, embrace a strategic and thoughtful approach. Find opportunities to voice dissenting opinions respectfully and constructively, backed by thorough research and evidence. Propose alternative solutions and demonstrate the value of fresh perspectives, leading with integrity, empathy, and determination. It’s hard to resist a well-prepared dissenter.

The Art of Everything for Everyone

Jean Dubuffet’s Closerie Falbala in Perigny, France.

What if we infused everything we do with Dubuffet’s way of thinking? This was a guy who could find artistry and forms of beauty everywhere.

In a pivotal moment in July 1962, as Dubuffet chatted on the telephone, he idly sketched with a ballpoint pen. This serendipitous act sparked the creation of intricate interlocking forms with linear shading, birthing his expansive Hourloupe series. Over the course of 12 years, Dubuffet dedicated himself to this mesmerizing body of work.

Between 1968 and 1974, Dubuffet finalized the Jardin d'émail (the Enamel Garden) in the heart of the Kröller-Müller Museum's sculpture garden in the Netherlands. Crafted from concrete, glass fiber, reinforced epoxy resin, polyurethane, and paint, this substantial artwork invites interaction, encouraging visitors to touch, walk through, and even play within its bounds. This project also opened the door for Dubuffet’s most imaginative and fantastical works, including the “Group of Four Trees” commissioned by the American banker and philanthropist David Rockefeller. Its black-and-white abstract trees measure 43 feet in height and remain installed in its original location in downtown Manhattan.

When Dubuffet was seventy, he unveiled his audacious Closerie Falbala, an architectural and artistic wonder sprawling over 17,000 sq. ft. in Perigny, about an hour south of Paris. It emerged as a walled landscape conceived to accommodate his Cabinet Logologique, envisioned as "a sanctuary for philosophical contemplation" — an immersive realization of his Hourloupe series. This colossal creation presents a radical departure from the traditional museum encounter and Dubuffet's embrace of "low taste" and art brut shines through in his whimsical, cartoonish sketches, influenced by the unpredictable currents of the subconscious.

“Without bread, man dies of hunger, but without art he dies of boredom... However, think particularly about the arts that have no name: the art of speaking, the art of walking, the art of blowing cigarette-smoke gracefully or in an off-hand manner. The art of seduction. The art of dancing the waltz, the art of roasting a chicken.”

Like Dubuffet, let's embrace the artistry of the everyday. Whether it's the finesse of a well-crafted email, the elegance of a persuasive presentation, or the creativity in problem-solving, let's recognize and celebrate that there’s beauty in the seemingly mundane. For it is in these small acts that we cultivate fulfillment, forge connections, and leave a mark on the world around us. Let’s learn to unlearn.